On November 25, 2019, the day the internet was abruptly cut off in Iran, it was not just a headline or a connectivity drop chart for Iranian users. I experienced it firsthand.

Not as “total darkness” in the sense that everything went offline, but as something stranger and more unsettling: a network that still appeared to exist, yet was no longer connected to the world. Domestic services, which are typically cloned versions of foreign platforms, worked sporadically. The browser would open and load, but Google would not connect. Instead, if you typed, for example, the letter “D” into the address bar, a domestic service like the online retailer Digikala would suddenly appear from the browser history. Connectivity existed, but access to the world did not.

That experience was confusing for many users at the time. The internet shutdown was neither like a power outage nor like ordinary filtering. Something in between had occurred: a form of separation from the outside world that simultaneously allowed parts of digital life inside the country to continue, in a limited and controlled manner.

During the 2022 protests, the government of the Islamic Republic demonstrated that its capabilities extend beyond a single, nationwide, and fixed blackout. Internet shutdowns can be implemented through targeted, regional, and time-based disruptions, a pattern that both enables repression and reduces the economic and administrative costs for the government.

When the internet in Iran was completely shut down in January 2026, what happened was no longer unfamiliar. The same logic was repeated: the outside world disappears, while inside the country, certain domestic or quasi-domestic services remain standing. The main difference this time was the quality of execution. The situation appeared more mature, more precise, and more normalized, as if the system had already completed its rehearsals.

It is this repetition that raises the central question. When the internet is neither merely filtered nor temporarily disrupted, but is fully severed from the outside world during moments of crisis, while a form of “minimal internal life” is preserved, does this trajectory ultimately lead to a model resembling North Korea?

What Is Iran’s National Information Network, and How Does It Work?

The Islamic Republic is building a distinct model of digital control and surveillance, one that is not based on permanent isolation but on conditional and interruptible connectivity. The central pillar of this model is the National Information Network (NIN). Unlike traditional physical infrastructure such as roads or factories, the NIN is not a static state project. Like other digital systems, it evolves continuously alongside advances in communications technologies, undergoes regular versioning, and is expanded in response to changing technical and political requirements.

To understand what is unfolding in Iran today, the NIN should not be examined through media narratives, nor primarily through reverse engineering by network engineers. A clearer picture emerges when it is read from the inside, through its own technical design and architecture documents, and with the mindset of a project manager. Two documents are decisive in this regard: Specification of the Requirements of the NIN (2017), and The Master Plan and Architecture of the NIN (2020).

These documents were adopted by an institution known as the Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC), the body responsible for overarching internet policy in Iran. The Supreme leader Ali Khamenei established this council as a parallel authority to the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in order to place strategic control of the internet directly under his oversight. His view of the internet has not been as an infrastructure for communication, e-commerce, development, or etc, but as a domain of “soft power competition” against what he describes as “global arrogance.” This ideological framework has shaped the logic of the National Information Network from its inception.

Definition of the National Information Network

In the official documents, the NIN is a managed and controlled infrastructure built on domestic networks, operating under the TCP/IP protocol, designed to support all of Iran’s connectivity, service, and content needs independently of the internet. In this definition, “independence” is not treated as an emergency or exceptional condition. It is articulated as a Guiding Design Principle. Within this framework, the connection of the NIN to the internet is not considered a mandatory epic, but an optional feature that can be restricted, controlled, or fully shut down without disrupting the operation of the national network itself.

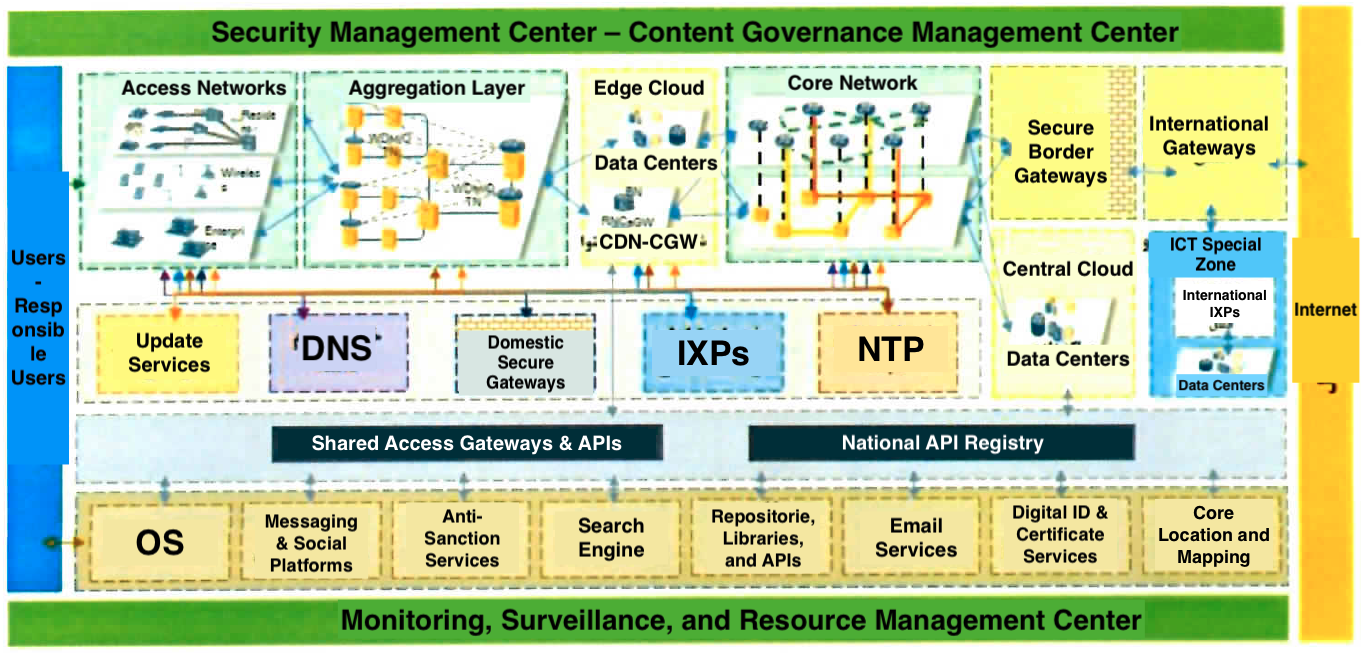

Figure 1. Technical architecture overview of the NIN, “Master Plan and Architecture of the NIN,” page 7.

From an architectural perspective, the NIN is not a single, unified network. It is a tree of networks organized across several clearly defined layers (light green frame). At the lowest level, the user connects to access networks. These can include mobile and fixed operator networks, ISP networks, or regional and provincial networks. At the next level, access networks feed into aggregation networks, where user traffic is collected and managed at a larger scale.

At this point, the architecture enters a layer referred to in the official documents as the Edge Cloud (light green frame). The Edge Cloud consists of data centers, CDNs, and related infrastructure that allow traffic between users on different networks across the country to be exchanged at high speed without passing through the core network and without requiring centralized connectivity. This design clearly indicates one of the primary objectives of the NIN: reducing dependence on central and international routes for the circulation of domestic data.

At the top of the network hierarchy sits the Core Network, where all networks converge. This layer is managed by the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company (TIC), a subsidiary of the Ministry of ICT. Within the core layer, the Central Cloud handles data exchange at the national scale, and high level traffic control, blocking, and censorship policies are enforced. As shown in the schematic, the path between the user on the left and the internet on the right is not direct. It passes through Secure Border Gateways, which function as chokepoints for control and filtering. These gateways connect the NIN to the international gateway, through which external connectivity is established.

The design documents explicitly refer to Internal Secure Gateways operating within both the access network layer and the core network. These gateways enable the enforcement of control, filtering, and censorship policies entirely within the domestic network, independently of any connection to the internet.

The NIN Services Layer and the Islamic Republic’s Digital Realm

Built on top of this communications and information infrastructure is the second layer of the National Information Network, which the official documents defined as National Network Services. This layer includes foundational services such as data centers, naming and addressing services, messaging, search engines, cloud services, APIs, and similar infrastructure components. Contrary to common assumptions, these services are not necessarily the same consumer facing or commercial services that everyday users directly interact with. The distinction between these two categories is made explicit in the architecture documents.

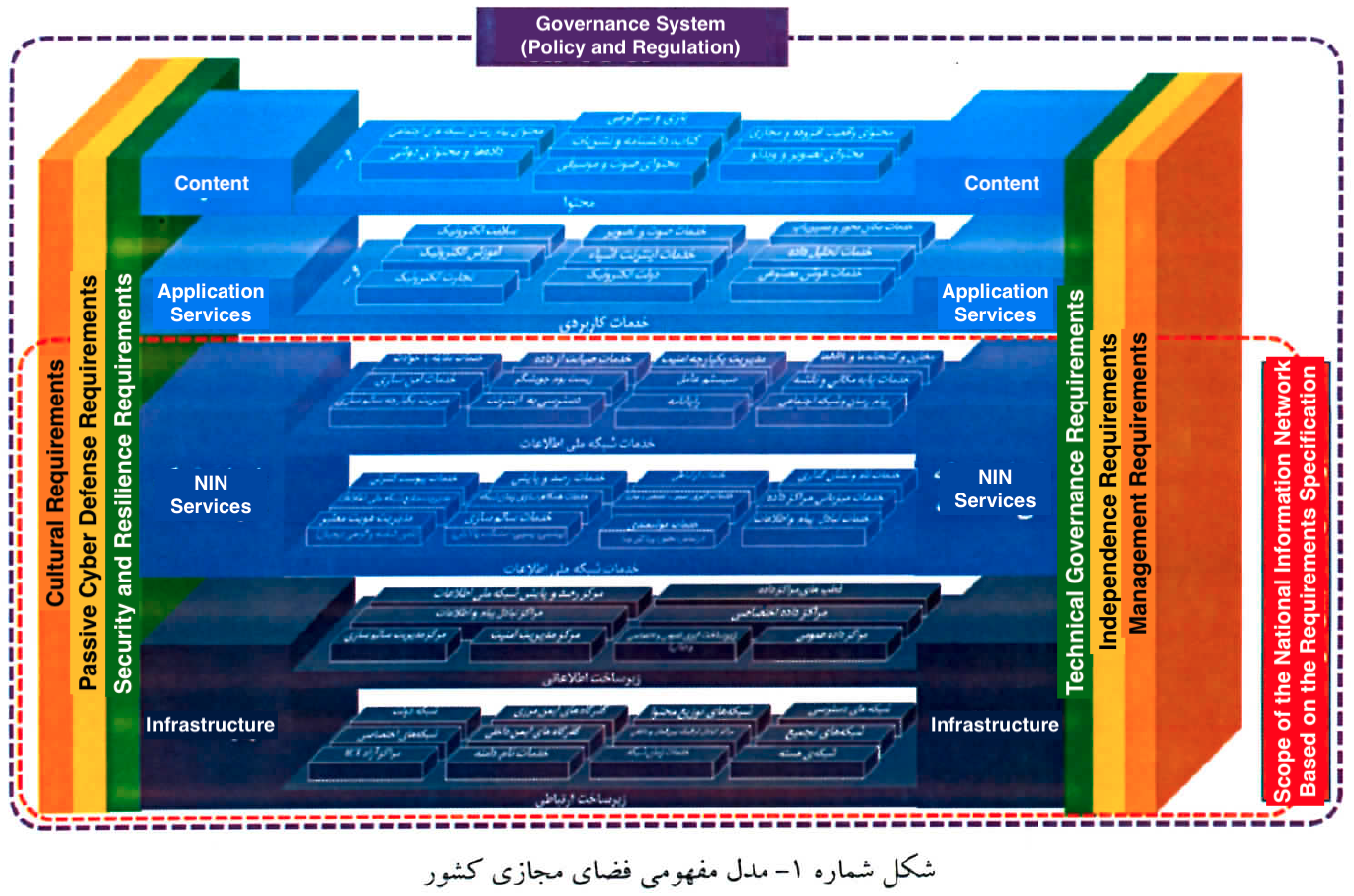

In the conceptual model of the country’s digital space, the government of the Islamic Republic defines a specific boundary as its “sovereign domain in cyberspace.” Within this domain lie the two layers of the NIN: the infrastructure layer and the national network services layer. This separation has practical operational significance, because it clarifies which systems, companies, or products are considered part of the National Information Network, and which merely consume services from it. For example, location based services or digital commerce platforms that operate at higher layers are not necessarily part of the NIN itself. By contrast, providers of core cloud services, foundational platforms, and infrastructure that operate within the national network services layer or the underlying infrastructure are directly situated within the NIN’s domain.

Figure 2. Conceptual model of the country’s Cyberspace, “Master Plan and Architecture of the National Information Network,” page 7.

A defining feature of this architecture is the structural distance it creates between the user and the internet (End of left and right boxes of Figure 1). Unlike a simple and direct connection, the user must pass through a series of layers, chokepoints, and intermediary systems before reaching the internet: Access Networks, Aggregation Networks, the Edge Cloud, the Core Network, and Internal and Border Secure Gateways. This distance is neither accidental nor merely technical. It is the result of a deliberate design that makes connectivity inherently manageable, interruptible, and reconfigurable.

Operational Objectives of the NIN

The Requirements Specification explicitly sets out the operational objectives of the NIN, with a deadline for achieving them set for March 2026. An examination of these objectives shows that while many developmental and quality related goals have not been met, the objectives related to oversight, control, independence, and access restriction have effectively been realized. These include the deployment of monitoring and oversight systems, the enforcement of control policies across all layers of the network, and the ability to operate the network under conditions of external connectivity disruption or limitation. This mismatch is not accidental. It reveals which aspects of the NIN have been treated as operational priorities by the SCC.

Taken together, these documents point to a clear conclusion: the NIN is neither a purely service oriented project nor a simple “national intranet.” It is an independent communications architecture designed from the outset to function sustainably in the absence of the internet. After years of incremental development, it has now reached a level of operational maturity that allows it to manage the country’s digital life under conditions of shutdown, disruption, or widespread access restriction.

How Internet Shutdowns in Iran Actually Happen

Internet shutdowns in Iran are neither technical malfunctions nor sudden decisions taken at the level of telecom operators. What occurs in practice is the result of a centralized security order, executed through a clearly defined chain of decision making, enforcement, and technical implementation. The Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), a body under the control of the Supreme Leader and the country’s highest security decision maker, along with its subordinate institutions, determines the national security level.

Just as, during street protests, the special units of FARAJA (Iran’s police) play a central role on the ground, and at higher levels the IRGC Ground Forces then special units enter the real space, an equivalent mechanism operates in the “cyberspace” the term used by the Islamic Republic to describe the internet. In this domain, policies are implemented through the Security Management Center (the green band in Figure 1). This center spans all layers of the network. It can set access levels locally, at the city or provincial level, across fixed or mobile networks, or nationwide. Its primary instruments for policy enforcement are the internal and border secure gateways shown in the schematic.

This is a conceptual model. The Security Management Center depicted in the diagram corresponds, in practice, to sub bodies of the SNSC and its joint committees with the SCC both under the influence of ayatollah himself. The border secure gateways are managed by the TIC, while parts of the censorship and restriction process, particularly within the domestic network, are implemented by mobile operators (carriers), ISPs, and data centers through internal secure gateways.

The process begins with a security assessment. At moments when the government of the Islamic Republic faces mass protests, civil disobedience, or crises of legitimacy, the internet is redefined not as a communications infrastructure but as a security risk. This redefinition quickly translates into a political decision to restrict or shutdown external connectivity. At this stage, the internet, as a base service within the second layer of the NIN, is shut down.

Experience shows that the security level at which a full shutdown of all networks is enforced through border secure gateways almost always coincides with severe violence and the killing of protesting citizens in the streets. The only exception has been the complete internet shutdown during the Israeli attack in June 2025. This simultaneity is not accidental. The experiences of Bloody November 2019, the autumn 2022 protests, and the national uprising currently unfolding in January 2026 demonstrate that internet shutdowns or severe degradation occur precisely at moments when the Islamic Republic resorts to widespread violence. The primary objective is not merely to control domestic communications, but to eliminate global oversight. Shutting down the internet lowers the political cost of violence, makes documentation more difficult, and buys time.

Within this framework, the internet is not only shut down; it is removed from view. Media connectivity, international coverage, and access by human rights organizations to field information are disrupted. This is why internet shutdowns are not a sign of strength. They are a sign of a crisis.

From the 2019 Blackout to Gradual Degradation in 2022

In 2019, internet shutdowns in Iran were experienced as a sudden, nationwide blackout. Connectivity to the outside world nearly disappeared entirely, while only a limited set of domestic services remained partially operational. Iran’s economy, however, proved unable to withstand a prolonged disconnection from the internet, and access was gradually restored. The underlying reason was that, prior to November 2019, the practical importance of the NIN’s basic services layer had not been truly tested (the middle layer in Figure 2). When the internet, treated as a core service within the NIN, was switched off, the network’s fundamental and operational deficiencies became unmistakably clear.

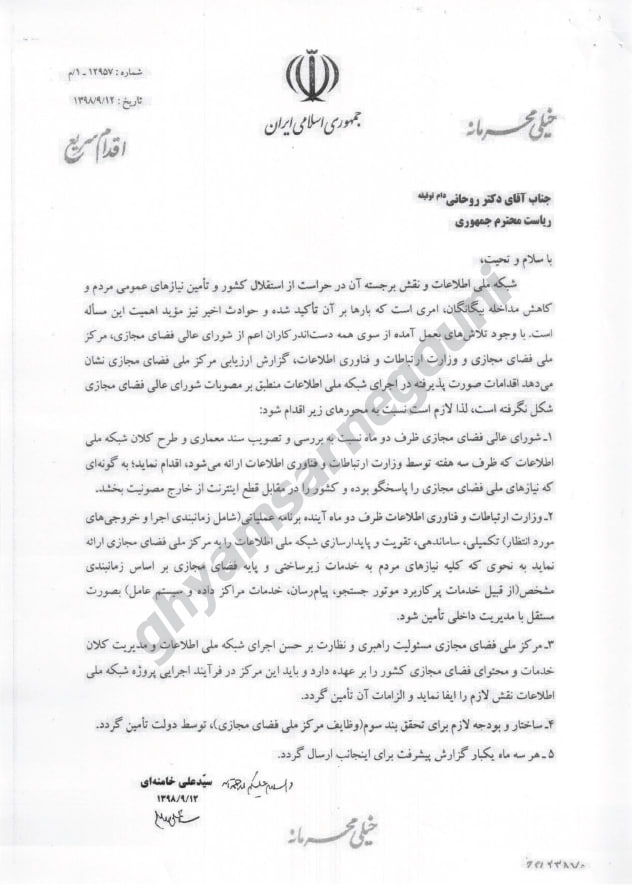

Two weeks later, Ali Khamenei addressed then President Hassan Rouhani in an unusually harsh and unprecedented letter, granting the Ministry of ICT a two-month deadline to present a plan for expanding the NIN’s core and infrastructural services in order to “immunize the country against internet cutoffs from abroad.” The Supreme Leader personally emphasized the development of a domestic search engine, a national messaging platform, data center services, and a national operating system. This letter was later leaked by hacktivist groups during the 2022 protests.

In this newer model, the internet is not necessarily shut down; instead, it is degraded. Access to foreign services is disrupted, connectivity becomes unstable, packets are dropped, and the user experience deteriorates sharply. At the same time, some domestic services remain operational. This is the condition many users describe as the “national internet.”

This is a deliberate choice. A total blackout carries high economic and social costs. Gradual degradation allows the government to disrupt sensitive communications while preserving a minimal level of digital life. The NIN was designed precisely for this scenario: maintaining internal functionality while shutting down or constraining external connectivity.

Under degraded conditions, the services that typically continue to function are those that either sit within the NIN services layer or are deemed by the authorities essential for maintaining a baseline of economic and social order. Domestic core services, local cloud infrastructure, certain messaging platforms, and systems that do not depend directly on the internet are thus able to continue operating.

Nationwide Internet Shutdown During the National Uprising, January 2026

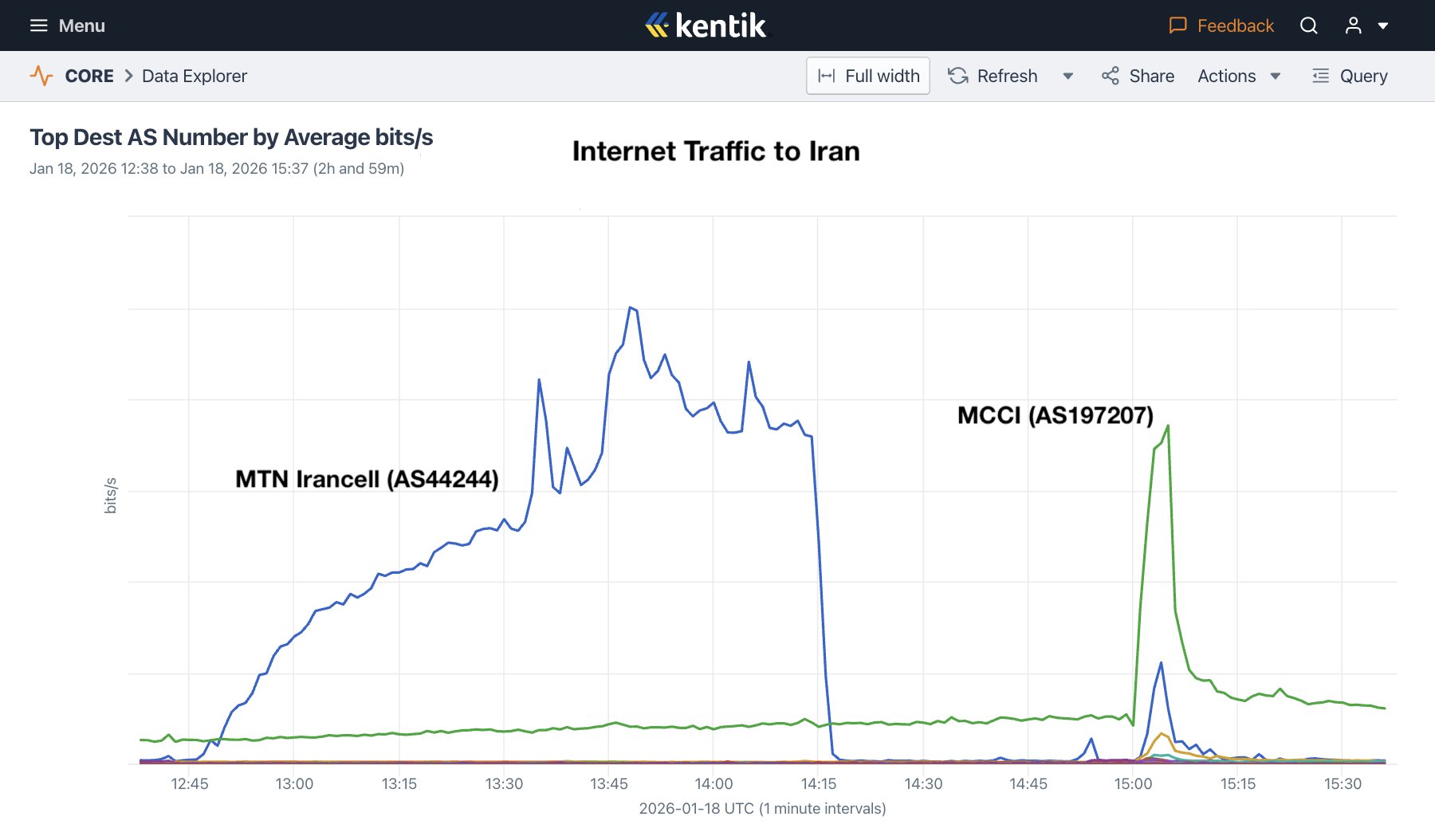

In the third week of January 2026, more than a week after the start of the complete internet shutdown in Iran during the latest wave of nationwide protests, traffic patterns emerged that at first glance could be interpreted as signs of a gradual return to normal connectivity. Traffic graphs from several operators, including brief and unstable spikes in inbound and outbound data, appeared to support this interpretation. These signals, however, proved short-lived and fully subsided after only a few hours.

These fluctuations were neither the result of random technical disruption nor an indication that restrictions were being lifted. What occurred in practice stemmed from a deliberate decision by the Islamic Republic to selectively and tightly reopen a limited set of service-oriented and functional applications, services deemed essential for maintaining a minimal level of economic and administrative activity. Implementing this decision required shifting part of the traffic control and filtering process from the Central Cloud at the core network layer to the Edge Cloud at higher layers of the network.

More precisely, during this phase, filtering and access-control mechanisms were not fully removed from the core. Instead, portions of these functions were relocated to the Edge Cloud, where data centers, CDNs, and policy enforcement systems operate at regional and operator-specific scales. This architectural shift makes it possible for certain predefined services to become accessible in a limited manner without reopening a full path to the internet. At the same time, primary control is preserved, and the system retains the ability to rapidly revert to a complete shutdown if required.

The traffic volatility observed during this period can thus be understood as part of a process of testing, updating, and synchronizing policy servers within data centers (the light yellow boxes in Figure 1). Such processes are naturally accompanied by temporary increases and decreases in traffic and do not, in themselves, indicate a durable change in users’ access conditions.

Alongside the shutdown or severe degradation of public internet access, developments in recent weeks show that the government of the Islamic Republic simultaneously requires a form of stable external connectivity to carry out specific cyber and intelligence operations. Unlike ordinary users, not all external connections are blocked during periods of crisis. Parts of the network are deliberately kept active.

In recent days, clear signs have emerged of the launch and escalation of cyber intrusion and offensive operations attributed to the Islamic Republic both at the level of infrastructure attacks and in the form of targeted operations against human rights activists, journalists, and political opponents outside the country. Such operations are inherently impossible without direct and sustained access to the internet. This fact alone demonstrates that “internet shutdowns” in Iran have never meant the complete severing of all external routes.

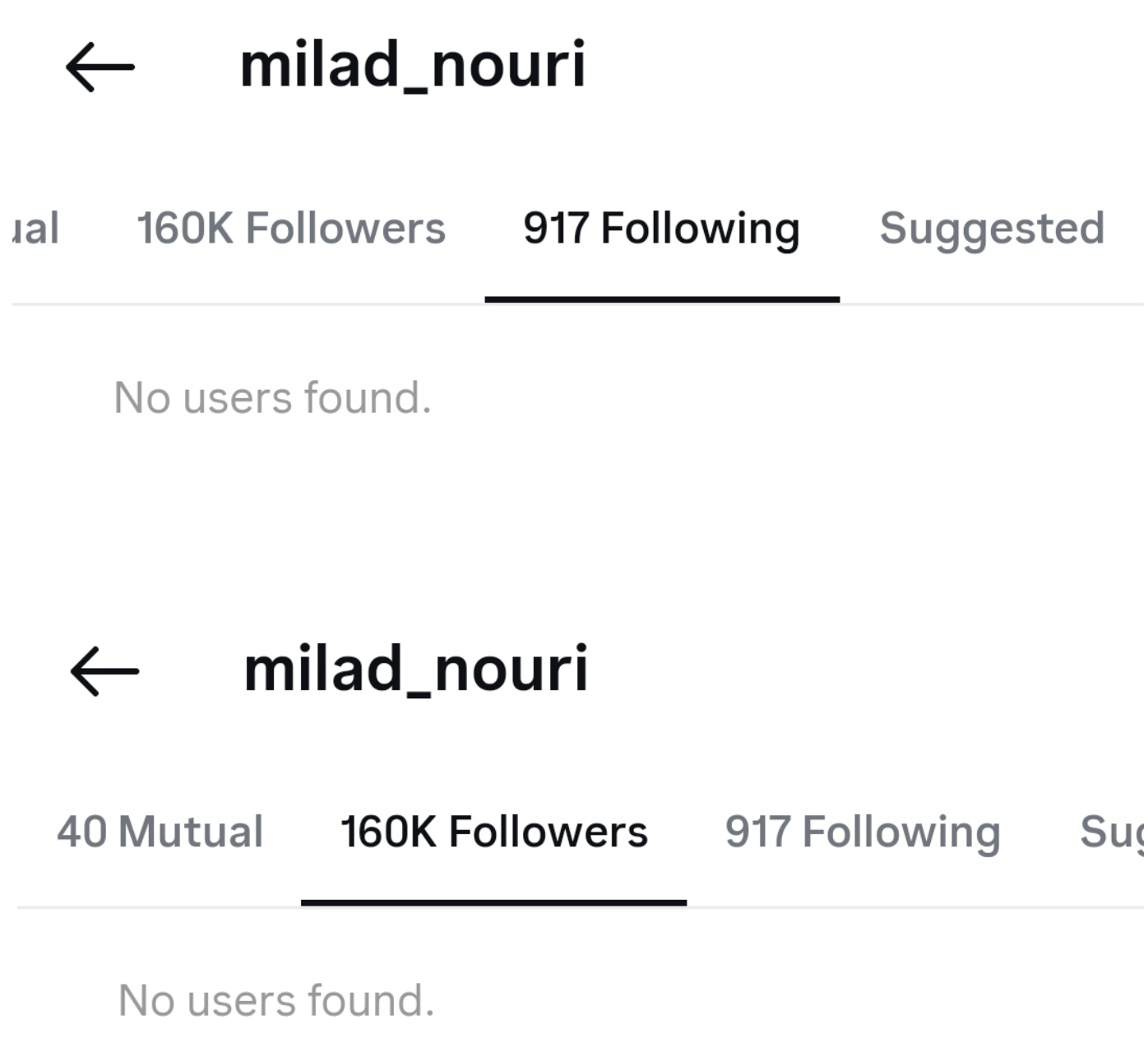

At the same time, evidence has surfaced indicating a heightened focus by intelligence agencies on harvesting social data from users, particularly on platforms such as Instagram. In a post on X, Cloudflare reported detecting abnormal behavior involving bulk extraction of follower lists and monitoring of account activity by tools attributed to the Islamic Republic of Iran. In response, Meta restricted certain Instagram features for users connecting from inside Iran. Meta’s action itself points to the presence of organized, non-consumer traffic originating from Iran and directed at the company’s infrastructure.

This type of connectivity is established neither through public access networks nor through the standard paths used by ordinary users. Under the NIN architecture, these connections pass through the “Special ICT Zone,” an area that, as shown in the architectural schematic (the blue box on the right side of Figure 1), is directly connected to the international gateway and positioned behind secure border gateways. In practice, this zone provides a privileged and segregated route for specific governmental, security, and infrastructure-related communications with the outside world.

Within this model, the shutdown of the internet for the general public coexists with the continuation of selective connectivity for security and operational institutions. For citizens, the internet is redefined as a security risk and restricted accordingly. For the same power structure, however, it remains an active, essential, and readily available tool. This duality is not a contradiction; it is a core feature of the NIN’s design: separation of access, separation of routes, and separation of the right to connect.

As a result, what is observed during internet shutdowns is not a “blackout,” but a reconfiguration of access. A network that goes dark for ordinary users is simultaneously kept lit for cyber operations, cross-border surveillance, and information activities. This reality once again underscores that the primary objective of cutting the internet is not to eliminate the internet as a technology, but to remove it from public access.

Conclusion: Is Iran Becoming North Korea?

Every time the internet is shot down in Iran, comparisons with North Korea quickly resurface in media coverage and on social platforms. While this comparison is emotionally understandable, it is analytically misleading, as it reduces Iran’s trajectory to an overly simplistic binary. To understand what is actually taking shape, it is necessary to distinguish among three authoritarian models: China, North Korea, and Iran.

In the model of the People’s Republic of China, the internet remains active but is heavily controlled. The Chinese government preserves connectivity because its economy, digital governance, and supply chains depend on a continuous flow of data. Censorship and surveillance are extensive, but the objective is to manage content and behavior, not to sever connections. The internet must function, even if it does so under strict control.

By contrast, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea represents a model of total isolation. The internet is effectively unavailable to citizens, and the domestic network functions as a closed substitute, fully separated from the outside world. This model is not designed for crisis management; it accepts isolation as a permanent condition, with its economic and social costs accounted for from the outset.

The Islamic Republic of Iran fits fully into neither framework. What has emerged in Iran is a model of conditional, crisis-driven connectivity. Under normal conditions, the internet is available, albeit filtered and unstable. During moments of political or social crisis, however, this connectivity can be rapidly degraded or cut altogether, while parts of domestic digital life continue to function. The NIN enables the precise operationalization of this model.

January 2026 marked a significant point in this trajectory, not because of any novelty in the nature of internet shutdowns, but due to the operational maturity of this approach. What occurred at this stage was not a radical break from the past. The model was first tested in 2019 and further developed in 2022. The difference in January 2026 lay in the quality of execution: greater technical precision, stronger institutional coordination, and an experience that felt less shocking and more familiar to users. Global connectivity was cut, but certain domestic pathways remained open. This time, a complete shutdown appeared less like an exceptional event and more like a recurring condition.

From this perspective, the question “Is Iran becoming North Korea?” is not the right one. In some respects, this model is more dangerous than total isolation. Under permanent isolation, boundaries are clear, and the absence of the internet is recognized as an imposed and abnormal condition. Under conditional connectivity, however, the boundary between being online and offline becomes blurred.

For this reason, focusing on comparisons with North Korea obscures the core issue. What is taking shape in Iran is not an imitation of Pyongyang, but the consolidation of a third authoritarian model. One that seeks to balance the need for connectivity with the desire for control. This balance is fragile, yet attractive to the government of the Islamic Republic, because it allows the internet to be opened or closed depending on political circumstances, without incurring the permanent costs of isolation. The consequences of this model for freedom of information and the future of connectivity in Iran are profound and long-lasting.