In recent months, Iran has become one of the main theaters of a quiet but decisive confrontation: the struggle to control the electromagnetic spectrum.

From well before the Iran-Israel war in June 2025, repeated reports of disruptions to positioning and satellite signals, combined with warnings from Iran’s free internet activists and growing attention by global media to Starlink jamming, have drawn a clear picture. The Islamic Republic is not merely censoring information. It is actively expanding technical tools designed to blind independent communication channels, including those that bypass traditional control infrastructures. In this context, what does a “jammer” mean in Iran, and who exactly is building and deploying it?

What Is Jamming? The Technology of Disruption and the Logic of Information Control

Jamming refers to the deliberate disruption of radio, satellite, or positioning signals and, in technical terminology, falls within the domain of electronic warfare. In Iran, however, this technology has long moved beyond a purely military framework and has been repurposed as a tool for controlling information flows. This shift aligns with the Islamic Republic’s overarching leadership doctrine, which frames the sphere of public opinion as a battlefield of “soft war.” Within this worldview, jamming is not a temporary or exceptional measure, but part of a durable architecture of power, one in which technology, security policy, and the defense economy are tightly interwoven.

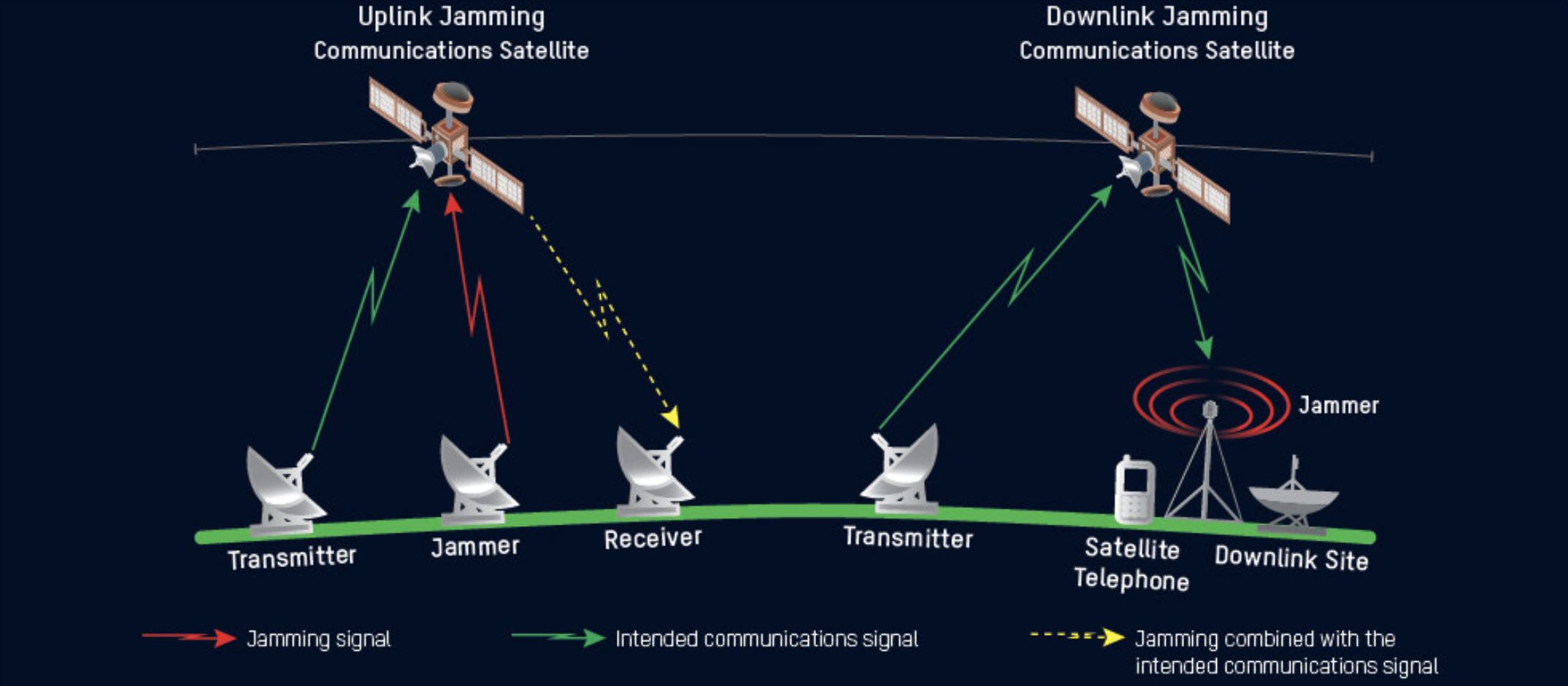

From a technical perspective, jamming involves injecting high power interfering signals into a specific frequency band so that the original signal can no longer be reliably received, decoded, or used. This interference can take multiple forms, ranging from broadband noise that blinds an entire frequency range to more targeted jamming designed to disrupt a specific signal, such as GPS, satellite communications, or data links.

In more advanced configurations, jamming systems can operate adaptively: detecting active frequencies, rapidly switching bands, increasing power output in real time, and even mimicking the original signal to induce errors in the receiver. For this reason, modern jamming is no longer merely a matter of a “high power transmitter.” It is a composite of radio frequency hardware, control software, and detailed knowledge of communication protocols, a combination that makes it a complex and costly instrument in electronic warfare and communications control.

In this sense, a “jammer” is no longer just a device or a standalone technology. It constitutes part of a broader strategy aimed at asserting control over the electromagnetic spectrum and suppressing independent communication channels, a strategy that is directly embedded in the security and defense decision making structures of the state.

Satellite Jamming: From Electronic Warfare to Cancer Scare Speculation

At the military level, satellite jamming is specifically designed to disrupt satellite based navigation, communications, and data systems, a domain that plays a decisive role in electronic warfare by shaping operational superiority and battlefield control. Interfering with positioning systems such as GPS can undermine navigation, timing, and coordination, not only for military units but also for civilian infrastructures that depend on these signals. Available evidence suggests that in recent years the Islamic Republic of Iran has deliberately invested in this layer of electronic warfare, developing systems focused on disrupting V and UHF communications as well as satellite navigation.

A defining feature of Iran’s newer jamming systems is the shift toward hybrid models that combine communications monitoring with active interference. A notable example of this approach is the system known as “Raad 500,” associated with the Army of the Islamic Republic of Iran. According to publicly available information, this system is capable of identifying, analyzing, and then adaptively disrupting communications and satellite navigation bands within a single integrated framework. By continuously surveying the electromagnetic environment, selecting targets, and applying tailored interference, such systems complete the classic electronic warfare cycle and elevate jamming from a static, reactive measure to an active component of a comprehensive communications control architecture.

The consequences of this form of jamming are not confined to the military domain or to satellite television broadcasting. Reports point to disruptions in maritime and aviation navigation, heightened safety risks, and cross-border spillover effects, disruptions that can affect transport chains, traffic safety, and even essential civilian services. From this perspective, satellite jamming is not merely a military capability, but a tool with direct security, economic, and human implications, one that blurs the line between defensive use and interference in civilian life.

During the 2010s, as the deployment of satellite jamming systems expanded into urban areas, concerns about their potential impact on public health also emerged at the expert level, while the phrase “cancer tsunami” entered public discourse. The issue of possible health effects from jamming systems was even raised within the Tehran City Council, where some members called for technical reports from the relevant authorities. According to public statements, such reports were prepared within official bodies, including parts of the public health system and government-affiliated research centers, but their findings were never released in a transparent and public manner. The involvement of formal institutions indicates that the biological implications of jamming were, at least at one point, treated as a technical and investigable issue.

Jamming in Iran: From Technical Project to a Security Governance Architecture

Jamming in Iran is not the result of the initiative of a single institution, nor a temporary reaction to an isolated communications crisis. Available evidence suggests that these technologies have been developed within the framework of formal and semi-formal policies of military and security bodies, particularly the Ministry of Defense, and have gradually become part of a broader toolkit of security governance.

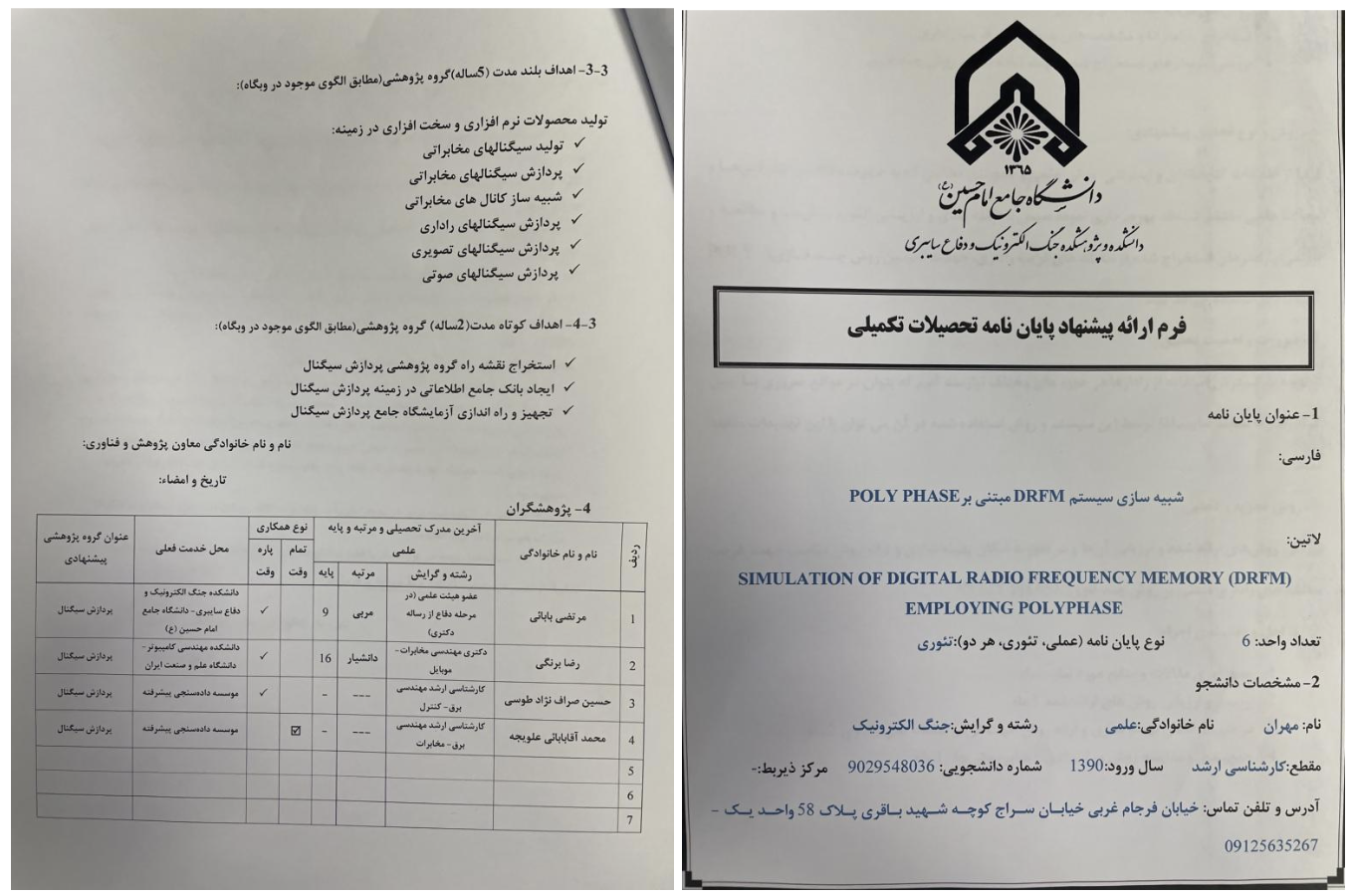

Within this model, the Ministry of Defense functions not only as the end user of jamming systems, but also as a regulator, coordinator, and agenda setter for electronic warfare projects. Key roles in research and development are played by major defense linked ICT entities such as SAIRAN, along with technical faculties at Imam Hossein University, affiliated with the IRGC, and Malek Ashtar University of Technology, which operates under the Ministry of Defense.

An examination of trends over the past two decades shows that as satellite media, the internet, and independent communication tools have expanded, the use of jamming in Iran has also increased in scale, complexity, and impact. The emergence of technologies such as Starlink, which bypass many domestic control mechanisms, has pushed this trajectory into a new phase, one that would not have been possible without the formation of a coordinated network of contractors, technical actors, and managerial structures.

In this new environment, jamming is no longer a marginal tactic or an emergency response. The deliberate disruption of communication signals has become embedded in the logic of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s security governance. This logic is aimed not merely at military defense, but at containing cross border media, neutralizing emerging communication technologies, and managing political crises at critical moments.

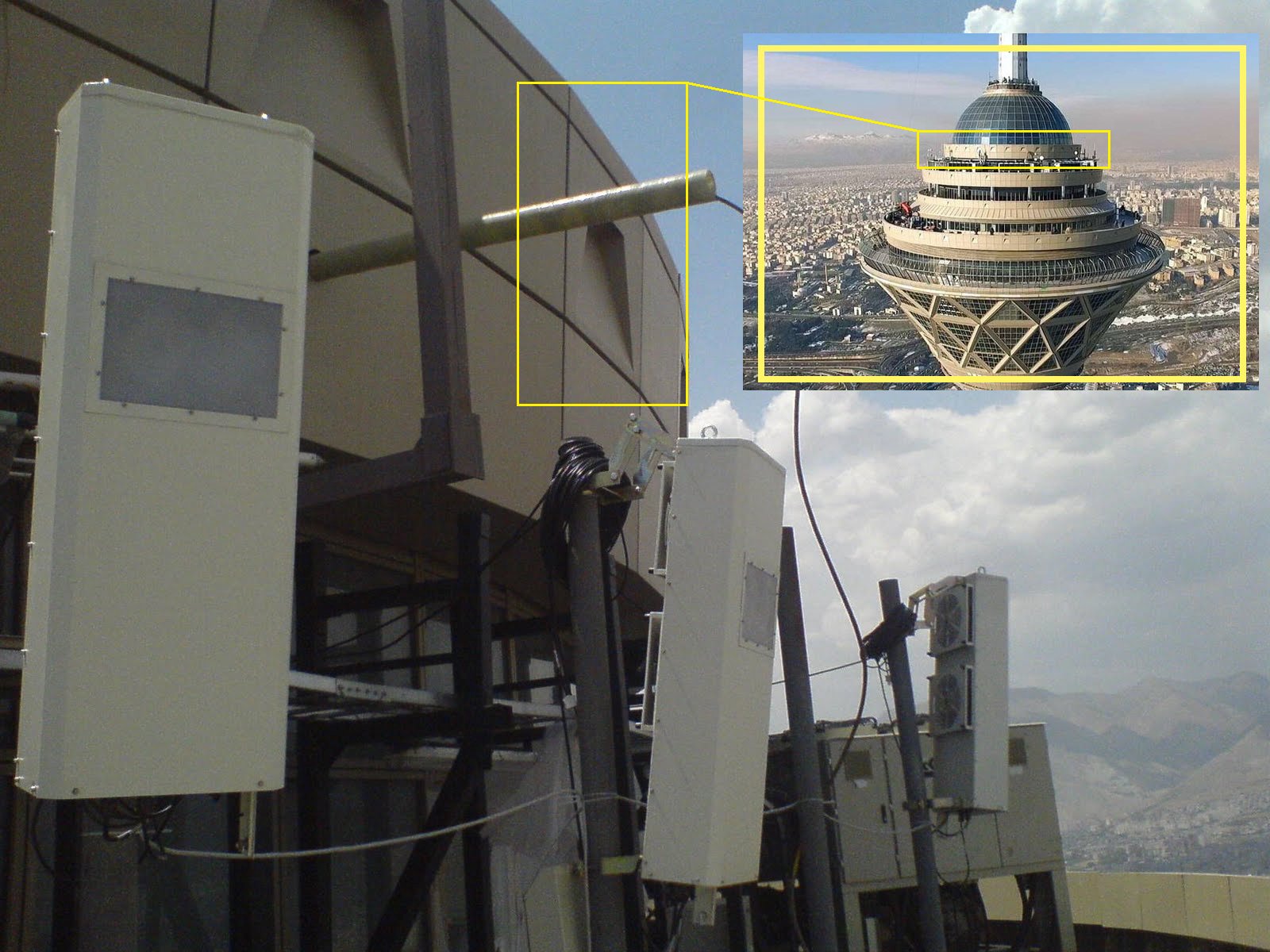

Above Milad Tower: Ofogh Saberin at the Core of Jamming Operations

Milad Tower, a 435 meter tall multi-purpose tower in Tehran should be understood as one of the central nodes for the deployment of jamming systems in Tehran. The release of technical data and field evidence related to the installation of the “Raad 2/1” system atop this structure brings the project’s executive contractor into focus: Ofogh Tose’e Saberin Engineering Company.

To understand the nature of Ofogh Tose’e Saberin, it is necessary to return to the institutional environment in which the company emerged. From the mid 1990s, and in parallel with the expansion of the economic activities of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in the post war period, a series of entities known as Co-op Foundations were established with the stated purpose of providing financial support to personnel of IRGC. Over time, however, these co-ops moved beyond a welfare function and evolved into major economic actors, tasked with financing sensitive projects and implementing strategic programs, particularly in sectors where the state could not intervene directly due to legal constraints or international sanctions.

Ofogh Tose’e Saberin Engineering Company was formed within this framework, as part of the portfolio of specialized firms affiliated with the IRGC Co-op Foundation. Registering such companies as private joint stock companies allows them to remain largely outside public oversight mechanisms, including state financial supervision, while effective ownership remains in the hands of sovereign institutions. This dual structure, private in form yet governmental in function, provides the operational agility required for classified projects, foreign procurement, and high risk activities.

Registration records and operational history show that Ofogh Tose’e Saberin is not a temporary, project based contractor, but a specialized firm active in defense electronics, telecommunications, and electronic warfare, operating within a stable network of affiliated companies. Its role extends well beyond the physical installation of equipment and includes system aggregation, technical integration, operational commissioning, and coordination with end user institutions. This profile distinguishes it from a conventional general contractor and places it closer to a semi governmental executive arm.

The composition of Ofogh Tose’e Saberin’s board of directors and its institutional ties to companies such as Moj Nasr Gostar Telecommunications and Electronics, Saberin Kish, and direct representation of the IRGC Co-op Foundation demonstrate that the company operates not on the margins of the formal state structure, but in continuity with it. This arrangement, commonly described as cross shareholding or circular ownership, serves two primary purposes: concealing the ultimate beneficiary and creating multiple layers of protection against sanctions. In practical terms, jamming projects are not implemented through genuine outsourcing, but through companies that carry a private legal identity while performing sovereign functions.

Board members and corporate representation of Ofogh Tose’e Saberin

- Mohammad Dehghani, Chairman of the Board, representative of Moj Nasr Gostar Telecommunications and Electronics

- Majid Mashhadi Ebrahim, Chief Executive Officer and Vice Chairman, representative of Saberin Kish

- Mohammad Yazdi, Board Member, representative of the IRGC Co-op Foundation

- Seyed Mehdi Ziaei, Board Member, representative of Pouya Electronic Research Engineers Pardis

- Mohammadreza Mohammadi, previously Seyed Mahmoud Ghotbani and Mohammad Hossein Rahedan, Board Member, representative of Baharan Gostar Kish

At the upper layer of this contracting network, executive management gradually gives way to institutional and decision shaping linkages. It is at this level that the role of figures such as Brigadier General Masoud Oraei, former chief executive of the company and current Deputy Minister of Defense for Logistics and Armed Forces Support, becomes visible.

Masoud Oraei: a logistics technocrat and architect of new defense relations

The professional trajectory of Brigadier General Oraei is emblematic of a class of technocrats who transition from managing specialized defense companies into senior policy making positions within the Ministry of Defense. His record as chairman of Ofogh Tose’e Saberin, board member of Saberin Kish, and participant in the Supreme Council of SAIRAN illustrates the depth of this institutional continuity.

Oraei’s promotion to the position of Deputy Minister of Defense for Logistics and Armed Forces Support marks a turning point in this trajectory. The Logistics and Support Deputyship functions as the logistical artery of the armed forces, responsible for equipment procurement, supply chain management, and strategic acquisitions. Placing an official with a background in sanctioned and front companies in this role underscores the Ministry of Defense’s reliance on experience drawn from the “gray market” and systematic sanctions evasion at a macro level.

In November 2025, Oraei acted as Deputy Minister of Defense and head of the Iranian delegation to the Joint Iran Belarus Military Technical Commission. In this capacity, he played a central role in negotiations aimed at establishing parallel supply chains, facilitating technology transfer, and enabling joint production under sanctions pressure. Cooperation with Belarus, a country possessing advanced electronics and optics industries while itself under extensive sanctions, illustrates how this network has evolved from a primarily domestic structure into an integral component of the Islamic Republic’s defense diplomacy.

Overall, Masoud Oraei can be seen as a symbol of the convergence between academia, industry, and the military establishment a convergence that grants projects such as jamming a form of technical legitimacy and reframes them from purely security-driven actions into engineered, institutionalized programs, even when their ultimate effect is the restriction of civilian communications.

The “Raad 2/1” System and the Logic of Area Denial Jamming

Images published from Milad Tower, together with an examination of the technical identification plates on the installed equipment, indicate that the deployed system is the Raad 2/1, manufactured by Saberin. This system is designed to provide wide-area urban coverage from a single, highly elevated location and, from both a technical and operational perspective, represents a classic example of area denial jamming in urban electronic warfare.

The Raad 2/1 falls within the category of fixed or semi fixed multiband jamming systems. It is likely configured through a combination of signal generators, high power amplifiers, and frequency filtering modules to produce effective interference across user level bands, including GNSS such as GPS and user satellite communications. From a technical standpoint, this architecture bears conceptual similarities to well known systems such as Russia’s Pole 21, which are designed to create navigation and communications denial zones through deployment on towers and other elevated structures.

The installation of multiple sector panel antennas on a high rise structure indicates a deliberate focus on controlling the directionality of radiated interference energy. Unlike large satellite dishes, these panel antennas are engineered to provide broad horizontal coverage with sufficient gain, enabling targeted disruption along urban line of sight paths. The selection of Milad Tower, whose height provides direct visibility across large portions of metropolitan Tehran, effectively turns the system into a tool for wide area interference against satellite and user oriented navigation signals.

Saberin Kish: The Commercial and Logistical Arm of the Jamming Network

Alongside Ofogh Saberin, which is primarily known as the technical executor and systems integrator of jamming platforms, Saberin Kish functions as the commercial and logistical bottleneck of this network. Without this role, the procurement, transfer, and sustained support of sensitive electronic warfare equipment would be practically impossible. A notable detail is the circular ownership structure: just as Saberin Kish holds shares in Ofogh Saberin, Ofogh Saberin is simultaneously a shareholder in Saberin Kish.

Company registration in the Kish Free Trade Zone is a core component of the sanctions evasion architecture. Free zones, with relaxed customs rules, more opaque financial pathways, and the ability to operate through foreign intermediaries, have become ideal hubs for importing dual use and sensitive goods. Even the company’s registered address in a commercial mall fits a well known shell company pattern: distancing the firm from its actual operational sites and dispersing its paper trail across crowded, publicly accessible locations.

According to a US Treasury statement issued on October 18, 2023, Saberin Kish played a direct role in the supply chain for components used in the Shahed 136 and Mohajer 6 drones. These items consist of dual use electronic components such as amplifiers, circulators, and inductors, elements that are critical to radar systems, flight control units, and precision guidance systems for drones and ballistic missiles. The ultimate end user of these components, according to OFAC documentation, was the IRGC Aerospace Force Self Sufficiency Jihad Organization, the backbone of the Islamic Republic’s drone and missile programs.

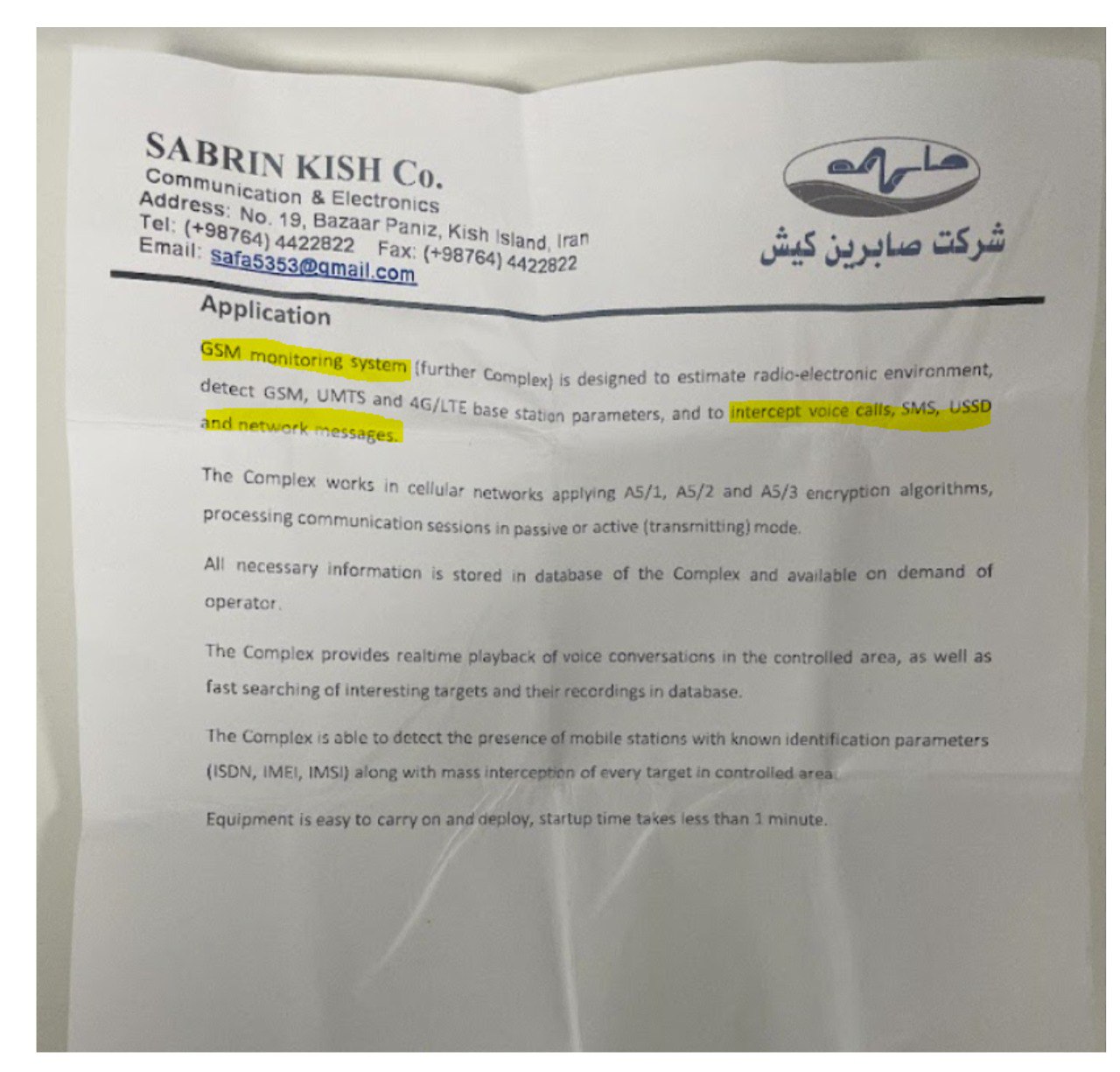

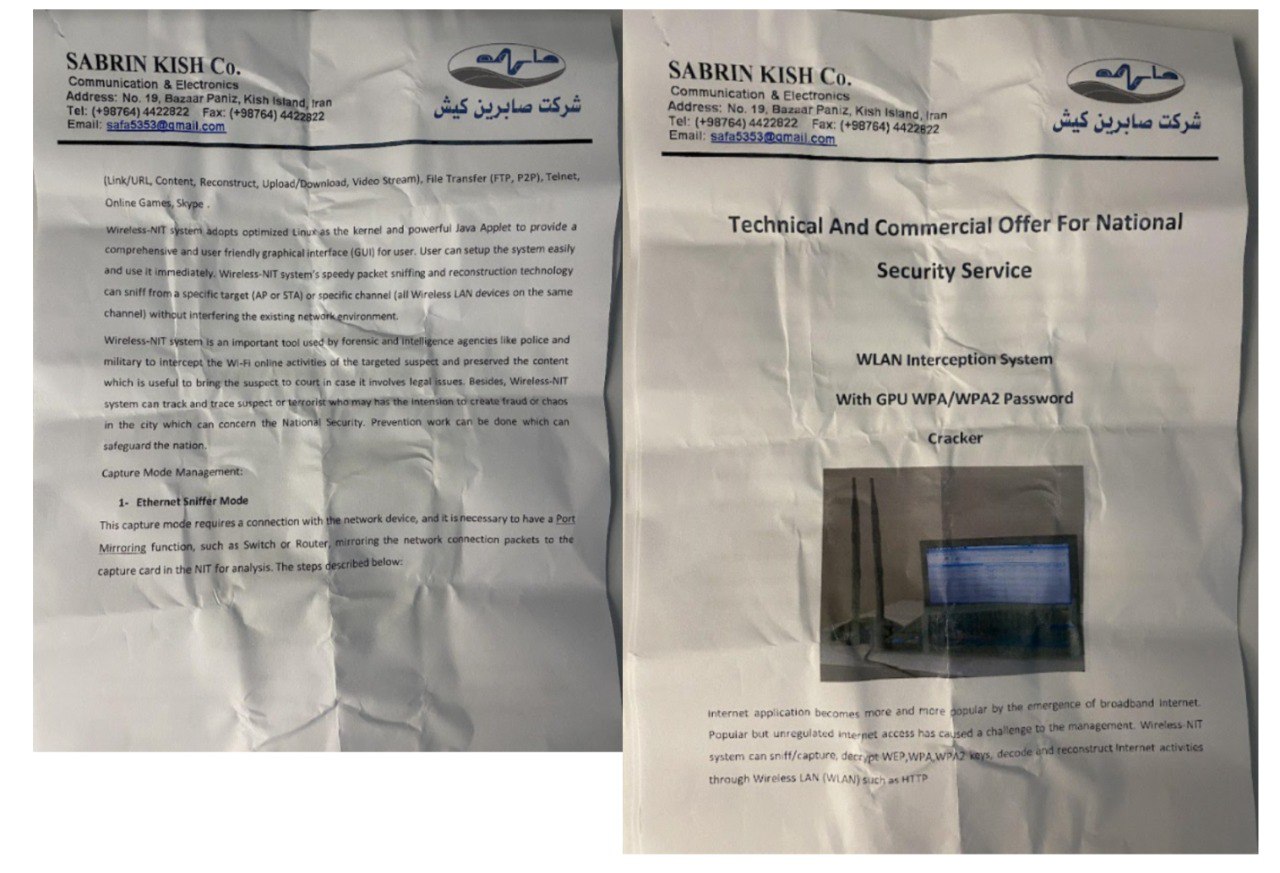

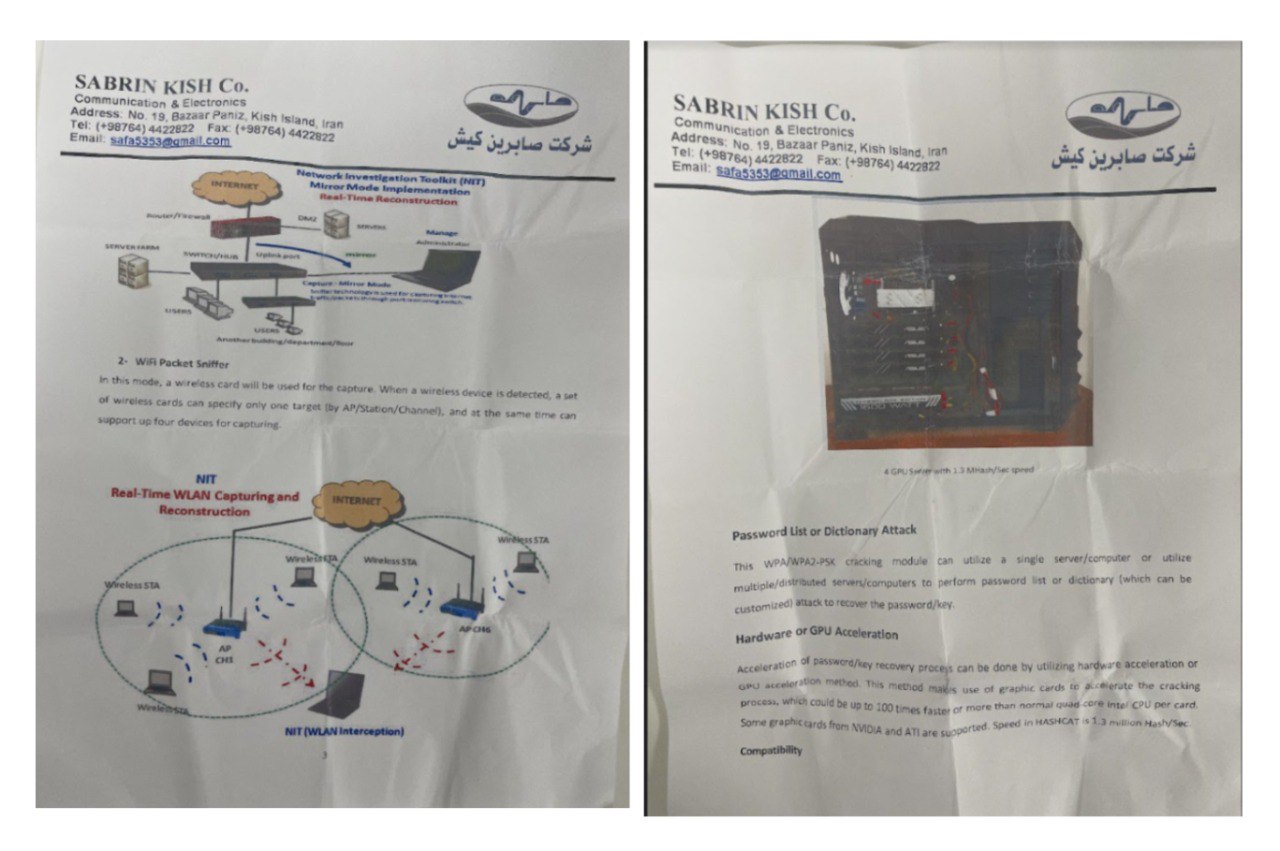

This chain, however, does not stop at hard military hardware. Reports by the hactivist group Lab Dookhtegan indicate that Saberin Kish’s activities extend into the realm of cyber surveillance and domestic espionage. Allegations include the provision of Wi-Fi interception tools, intrusion into home and office networks, and the supply of mobile-signal-based geolocation technologies. Cooperation with companies such as "Dade-e-Sanji Pishrafte completes this picture: an interconnected ecosystem in which component importation, jamming, drones, and digital interception are all linked within a single chain designed to control and suppress communications.

Shared Management Networks and the Engineering of Sanctions Evasion: From Boardrooms to the Global Gray Market

The management model linking Ofogh Tose’eh Saberin and Saberin Kish reveals a structure in which projects are not dependent on ad hoc individuals, but are advanced through a stable network of managers and operators.

At the center of this architecture stands Majid Mashhadi Ebrahim. Without a public profile or a formal military rank, he moves across technical, commercial, and managerial layers, holding senior positions in multiple companies either simultaneously or in sequence. His record within firms that have all been targeted by US Treasury sanctions points to practical expertise in managing complex supply chains, working through foreign intermediaries, and moving goods and capital via non-transparent channels. Carefully timed exits from executive roles and re entry into other boards as a legal representative form part of a classic tactic to diffuse sanctions pressure and prevent its concentration on a single individual or entity.

The scale of this network became clearer in October 2023, when Saberin Kish was sanctioned by the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. Documents show that Saberin Kish did not purchase sensitive components directly. Instead, it relied on a professional intermediary network designed for sanctions evasion. Alireza Matinkia was identified as the principal procurement broker. He received orders for sensitive US and Japanese origin components from Saberin Kish and routed them to a China and Hong Kong based network run by Lin Jinghe, also known as Gary Lam.

To give these transactions a veneer of legality, Gary Lam used several Hong Kong registered shell companies. Nanxigu Technology handled the direct procurement of electronic components from Western suppliers, many of whom were unaware of the ultimate end user. In parallel, Dali RF Technology functioned as the financial conduit, managing incoming and outgoing payments. After purchase, goods were shipped to Hong Kong, shipping documents were altered, and the cargo was then sent either via the United Arab Emirates or directly to Iran.

The financial pathway was equally engineered. Payments were routed through exchange networks and financial channels linked to the IRGC economic ecosystem, with funds deposited into accounts held by companies such as Dali RF at Chinese banks. From the definition of technical requirements by military engineers to procurement, transfer, and settlement, this cycle points to a fully formed sanctions evasion ecosystem. Individuals, domestic firms, foreign shell companies, and opaque financial routes all operate in concert toward a single objective.

As a result, the Saberin management network cannot be understood merely as a group of cooperating companies. What emerges is a coherent architecture for executing electronic warfare projects, information suppression, and weapons procurement. This architecture stretches from technical firms in Tehran and shell entities in Kish to paper companies in Hong Kong and bank accounts in China.

From Covert Importation to Operational Export to Iraq and Syria

Available technical and contractual documents indicate that the Saberin network is not limited to importing and supporting domestic digital repression systems. Over time, it has evolved into an operational exporter of surveillance, monitoring, and communications disruption technologies to governments aligned with the Islamic Republic of Iran. The primary focus of these exports has been Iraq and Syria, prior to the collapse of the Bashar al Assad government. Both countries provided favorable conditions for the transfer of such technologies due to internal security dynamics and political dependency.

At the core of this export portfolio are GSM monitoring systems designed to intercept GSM, UMTS, and 4G LTE networks, with capabilities including the interception of voice calls, SMS, USSD, and network signaling messages. These systems can operate in passive or active modes and are capable of live playback and archiving of communications. Explicit references to encryption algorithms such as A5 1, A5 2, and A5 3 in the documentation underscore that these tools are intended for intelligence and security environments rather than limited commercial or lawful use.

Alongside these systems, documents related to WLAN interception and WPA and WPA2 cracking tools show that Saberin has also been active in penetrating Wi Fi networks, reconstructing data traffic, and intercepting local internet communications. These are precisely the technologies used to monitor urban populations, identify activists, and control gatherings.

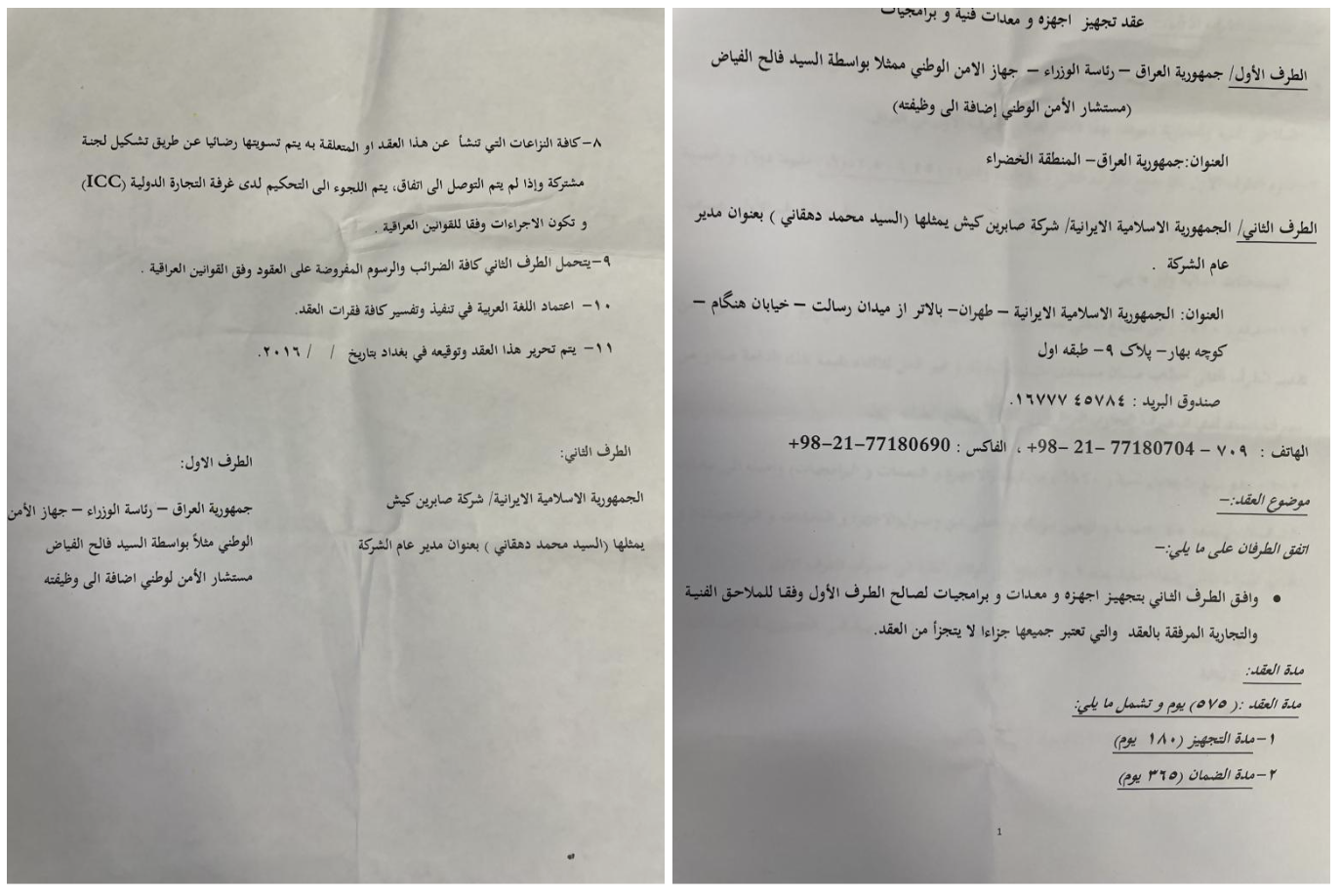

The most significant element of this file concerns contractual documents detailing the direct sale of equipment and services to the Government of Iraq. In one such contract, Saberin Kish is identified as the second party, committing to supply technical equipment and software to Iraq’s National Security apparatus. The implementation site is specified as Baghdad’s Green Zone, and the legal structure includes delivery schedules, warranties, and dispute resolution mechanisms. This is clear evidence of a formal state to state security contract rather than an informal transaction.

Taken together, these contracts show that technologies initially developed for domestic control inside Iran have been packaged and exported as ready made digital repression systems to Iraq, and previously to Syria.

The import of sensitive components from the United States and Japan through China, Hong Kong, and the United Arab Emirates, followed by assembly or systems integration inside Iran and eventual export to Iraq and Syria, forms a complete cycle of sanctions bound imports and security focused exports. Through this network, surveillance and jamming technologies that were first deployed to control Iranian citizens are transferred to aligned governments. This process simultaneously expands the Islamic Republic of Iran’s security influence and helps offset the costs of its domestic repression projects.

Final conclusion: Jamming as a hidden pillar of information repression

A case based examination of jamming in Iran shows that this technology is not a marginal or auxiliary tool, but an integral component of a broader system of information repression. Alongside internet filtering, communications interception, nationwide network shutdowns, and media control, jamming plays a complementary and in some cases decisive role by silencing channels that cannot be contained through other means, particularly satellite and wireless communications.

Analysis of the network linking Ofogh Tose’e Saberin Engineering Company, Saberin Kish, and their institutional ties to the Ministry of Defense demonstrates that jamming in Iran is not the result of ad hoc or reactive decisions. It is embedded within a durable security economy, one in which shell companies, defense contractors, academic layers, and sanctions evasion supply chains operate together to enable structural control over information.

In this framework, Ofogh Tose’e Saberin is an example rather than an exception. What matters is the architecture itself: political decisions are taken at the sovereign level, execution is delegated to networks of ostensibly private companies, and final control remains in the hands of military institutions. Interlocking ownership structures and circular shareholding arrangements complete this architecture of repression by concealing the ultimate beneficiaries and creating multilayered shields against international sanctions.